What do driverless cars mean for suburban planning?

February 16, 2015 5 Comments

Self-driving cars are coming, and boosters of drivable suburbia are hoping they will be a potent weapon against mass transit and cities. But what they mean for towns and suburbs isn’t quite so clear.

For the past 80 years, the US has transformed nearly every place in the country into one that is acceptable and welcoming to the personal automobile. It needs places to park (some estimates have that there are 6 parking spaces for every car), needs enough road space to be able to drive unimpeded, needs sole control over the roads, and so on.

In places built in the past 30 years, this has meant sidewalk-free eight-lane boulevards and massive malls at freeway interchanges. In places built before the car, this has often meant their wholesale destruction. (Santa Clara and Fremont, for example, are now undertaking efforts to “rebuild” their town centers.)

This has not been in service to the car as a vehicle, however, but to the car as a personal mobility tool. Very often, the only seat used in a car is the driver’s, massively enhancing the person’s footprint and leading to all kinds of horrific traffic.

With the advent of the driverless car, the belief is that we will no longer need personal vehicles, and this excess footprint will become unnecessary. Open up an app on a phone, order a car, and a vehicle (possibly with others in it going to roughly where you’re going) will drive by, pick you up, and drop you off near your destination. Along the way it’ll pick up other people going in roughly the same direction as you, bolstering capacity of the personal car to a grand total of five.

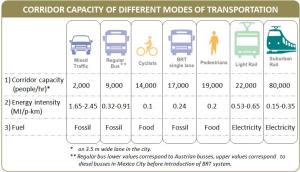

Five trips, one car. As one Twitter follower called it, it becomes mini-mass transit, but at the beck and call of an app and as flexible as it needs to be. If this method of travel becomes ubiquitous – and that’s a big if – then the personal automobile might become a thing of the past.

What, then, of the places we’ve outfitted at great expense to fit the personal automobile? These would need to be retrofitted to fit this new dominant mode, and we can do away with some of design choices that favored the personal automobile.

Probably the biggest change is the demise of the large parking lot. These huge slabs of asphalt dominate suburban commercial landscapes, often taking up 80 percent of commercial parcels. They dominate the streetscape, and arterial suburban roads are lined with them. Without personal vehicles to park, there’s no need for a parking lot. That land could be put to productive use.

With a transportation system that’s five times as efficient, too, there’s little need for wide arterial roads packed with single-occupant vehicles. As well, without human drivers, there’s no need for “forgiving engineering” focused on driver psychology and driver needs. We can narrow lanes from 12 feet (freeway width) down to 10 feet or even 9.5 feet and have the same vehicle capacity and speed. There would rarely be a need for roads wider than 2 lanes in the suburbs.

So, we can wave goodbye to parking lots and wide arterial roads. What could we do to optimize the suburbs to fit this new reality?

First, trip origins and destinations would be best served if they are along the same axis of travel, and they should be relatively evenly spaced and close together. Street grids lined with origins and destinations make sense, so as to maximize the directness of the travel. That means either a commercial street with homes behind or above.

With the loss of parking lots, it makes no sense to place storefronts far back from the street. They should be placed against the street to ease access for passengers.

Finally, there will likely be a need for a short walk to or from a vehicle, especially when returning home. It makes sense to make that walk a pleasant one, and to put amenities there, too.

It’s important our density not get too high. Although boosting car capacity fivefold is a huge step forward, trains have eight to forty times the capacity. For the highest-density areas, where trains are already at capacity, driverless mini-mass transit won’t be enough to solve congestion or to adequately meet residents’ travel needs.

So in the retrofitted suburbs, there should be a balance between the need for a dense line of origins and destinations and the need to not overload the system. Perhaps just six stories, at most, in the most dense places of the suburbs.

For this kind of system to work and not devolve into that kind of nightmare, it needs to have simple and easy lines of operations, just like the streetcars did, with origins and destinations located near stops. Unlike streetcars, the whole street is a possible stop. Rather than a series of one-dimensional stops surrounded by a station area, there is a two-dimensional transportation corridor surrounded by a transportation area. The station neighborhoods currently in existence could easily be integrated into suburban corridor fabric.

At this point, this does not sound much like the suburbia we often consider “suburbia”. With no parking lots, no wide roads, a street grid, and shops and homes clustered up against the sidewalk, it sounds more like a town center. That’s because this transportation cloud functions much more like the streetcars of the old days than personal cars of today. The urban landscape described is precisely the kind of bus-transit-oriented development that suburbs could be investing in today. This article could have painted just the picture: “Imagine standing at almost any street corner, where every five minutes an electric train bus vehicle comes by…”

Indeed, if this system ever does overcome myriad regulatory hurdles, it will work best in places where buses and light rail work best. If this is our dream future, then we can start planning for it today. There’s no need to wait for driverless cars.*

Of course, this system will likely be decades away, if it ever happens. There are huge regulatory hurdles to any driverless car, and any area where this system operates could be seriously disrupted by even one person driving their own car. As well, there are still questions of who owns and maintains the vehicles. In the interim, personally owned automated vehicles will likely start to ply the roads. (While they will reform how we use parking, they won’t do much about traffic.)

But if this system does come, it’s not something for champions of small towns, walkable living, and transit to fear.

*As people start to buy personal driverless cars, the need for vast parking lots will diminish. If we really want to start planning for that reality, too, then we should reform or abolish parking standards today.

AN ASIDE: This system has been speculated upon for decades as Personal Rapid Transit, or PRT, though generally it was theorized on rails. In fact, it already exists, in a sense, in Morgantown, West Virginia.

Much of the time, Morgantown’s system works like an elevator (push a button to summon a vehicle, push a destination button and you’re on your way). During rush hour, it operates like standard-issue fixed-route transit during peak hours, and in off-hours each car runs the whole track as a circulator.

FORGIVING ENGINEERING

Dave states: “there’s no need for “forgiving engineering” focused on driver psychology and driver needs. We can narrow lanes from 12 feet (freeway width) down to 10 feet or even 9.5 feet and have the same vehicle capacity and speed. ”

Human driven cars are going to remain for a long time. For instance contractors driving trucks. Stuck in the muds who enjoy driving. Perhaps some, but not all lanes can be narrowed. But you make a great point. Road capacity will steadily increase. This means that the need for (and value of) trains is vastly diminished.

DENSITY:

Dave states: “It’s important our density not get too high….” << I love this. I will be quoting you on this.

He continues: "For the highest-density areas, where trains are already at capacity, driverless mini-mass transit won’t be enough to solve congestion or to adequately meet residents’ travel needs."

Think this through – if adoption of the transportation cloud is sufficient many may abandon lengthy, connecting transit trips to shorter, door to door convenience.

OCCUPANCY – SUGGESTING A FIVE-FOLD INCREASE IS A FALLACY

Dave states: "Along the way it’ll pick up other people going in roughly the same direction as you, bolstering capacity of the personal car to a grand total of five."

Would hate for you to fall foul of the straw man fallacy. Average occupancy won't be 5, but it during commutes it can climb a long way north of the current 1.13 figure.

THE BIGGEST FALLACY:

Dave states: "For this kind of system to work and not devolve into that kind of nightmare, it needs to have simple and easy lines of operations".

This is simply wrong thinking. The transportation cloud is fluid and the need for simple arterials is no longer necessary. More to come.

I wasn’t commenting on your post specifically, but…

a) If you are calling on planning agencies to plan for this speculative future by ripping out or ignoring transit, then we should start doing road diets and parking reform today, too, to maximize the efficiency of the driverless car.

b) However, if you’re speculating instead that driverless cars will possibly *only* double the capacity of roads, then we’ll still have a HUGE need for transit. The downsides of the automobile revolution will still remain, while the upsides will be essentially the same, meaning any competitive advantage of cities will also remain the same. (The fact that it’s taking a half-trillion dollars per year to maintain the suburbs means it’s quite an advantage.)

All that is to say that either the transportation cloud will function like mini-mass transit, in which case the suburbs will likely become more dense (fyi, I meant “not too dense” as in “probably no more than 10x contemporary suburban densities”), or it will function like taxis and cars, in which case the planning status quo won’t really change.

The scenario of the future being posed is one is which services like Lyft and Uber use autonomous vehicles instead of human drivers. The question being asked is “what would happen to the suburbs with ubiquitous robo-taxis.” Dave speculates that people might not need to own or use their own cars, leading to a lessening of suburban asphalt. Richard Hall responds that robo-cabs will kill transit, since taxis are a superior service.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume away all of the legal and regulatory barriers to allowing cars to operate without a responsible party behind the wheel (what happens if a robo-taxi catches fire? can police pull them over? what if people get up to some anti-social things in them?)

The biggest problem with this conversation is the assumption that robo-taxis will grab some sizable share of the transportation market. There is really no basis for such a belief. Taxis exist right now and represent a tiny fraction of trips in our transportation system. People in rural and suburban areas almost never use them unless they are going to the airport. People use them more in big cities but, even there, most people can’t afford to use them very often.

As things stand now, in the suburbs, taxis offer no real comparative advantage over just owning your own car. If you had to use a taxi every day in Marin, you would be far better off financially just buying a Honda Fit or something. In most suburban areas there is no cost to park and no “garage fee” or cost of car storage. In a big city, a taxi has a couple of advantages over transit – it takes you door to door and you don’t have to park or store it. Great! However, when faced with a $50 taxi ride or a $2 transit ride, mere mortals are going to opt for the transit most of the time. Or walk/bike. Or, just use their car like any suburbanite would.

For robo-taxis to become a serious mode of transportation, they would need to have a much , much greater advantage over status quo taxis, relative to other options. Would they? I doubt it. At best, they could offer lower cost taxi service. With a robot, you save the labor of the taxi driver. However…you still have all the capital costs of taxis and the cost of fuel. Plus, you have a whole, complex system engineering operation that will require continual maintenance by people who earn way more than taxi drivers. God only knows what the insurance policies will be like.

If robo-taxis stop to pick other people up, that might help to make them cheaper to deliver (with the side benefit of higher auto occupancy) However, it also would make the service worse than a contemporary cab and more akin to a super-shuttle. I don’t care how efficient the algorithm is: robot super-shuttles are not going to replace personal vehicles in the suburbs.

Moreover, even if the cost of taxis could be brought way,way down, would it change things? Again, I doubt it. Even if Uber was half the price of today, most in the suburbs would still use their cars for local trips. They would also still use things like the ferry to get to the city since it would still be the most cost competitive option. The poor would still find local bus service to be the best deal to get around town. The robo-taxi would have to be dirt cheap to have a prayer of taking a tangibly bigger share of transportation trips.

And, why would we assume a future where robo-taxis are dirt cheap, but other modes somehow don’t become cheaper themselves. If cars are much cheaper in the future, it might help the bottom line of robo-taxis, but would also make it more attractive to just own a car and drive it yourself. And….. if robo-taxis are legal and work just fine, then why not robo-trains? Why would labor saving technology only work for private taxis using regular cars. If you take the driver out of transit, you take out 70% of transit costs. You could see the emergence of free public transit, or serious private transit services. A robo-bus operation with fixed routes and stops could be incredibly cheap to operate – much cheaper than robo-taxis.

In short, I don’t not see a niche for robo-taxis that will be much bigger than the current market for cabs in general. And, it’s the dominance of robo-taxis that is assumed in all these speculations about the future of suburbs. The economics of transportation choices is what’s missing in this discussion.

Pingback: Today’s Headlines | Streetsblog San Francisco

In the long term, I expect many people will shift from car ownership to subscribing to a fleet of self-driving vehicles (SDVs). This could lead to three market-based pricing benefits.

Firstly, people will be less committed to using a car for everything, as hey won’t have sunk a big piece of their life savings into owning one (or two or three).

Secondly, the capital cost of a fleet car is more likely to be amortized nd integrated into the mileage charge for using it.

Thirdly, the opportunity cost of the road space used could be easily calculated and billed, using the car’s navigational software. That would enable road usage costs to be tied to space and time – and therefore available capacity – rather than fuel or electricity consumption.

If these three benefits eventually occur, ndividual car trips will be more costly, but people will be freed from the assive up-front investment or ongoing car loan debt. This will provide a better market pricing signal for each decision on whether to use the fleet car or to use public transit.

Both these effects will tend to favour transit use for those trips for which it is most efficient.

Like other commentators, I also agree that there’ll be much less need for parking, which in turn will enable higher densities which will encourage both walking and urban transit use. SDVs will, in my opinion, affect car ownership and taxi services more than bus, tram, BRT or LRT in urban areas. In some ways, SDVs will help transit by removing the big parking issues that plague downtowns and favour sprawl. As others have noted, many people – at least in urban areas – will opt simply to subscribe to a fleet of SDVs which can be summoned by a simple cellphone call. By reducing parking demand, this will enhance density and make transit more efficient and attractive at the same time. Nevertheless, as others have already noted, marginal bus and rail services will

doubtless be replaced by SDVs, such as in outlying rural areas.

Trains, buses and trucks will also be able to drive themselves, and road vehicles would probably be able to have more trailers, as long as snow and ice don’t affect adhesion. I’d imagine passengers would still want someone on board an SDV train or bus, but the employee could

focus on passengers’ needs rather than driving – more like the old bus conductors. Of course roads, especially freeways, could become filled with multi-trailer trucks and buses with multiple bellows. Then again, vehicles could be spaced only inches apart, increasing capacity without

necessitating additional lanes. But freeway geometry and people’s stomachs will only tolerate design speeds. As a result I believe fast passenger rail will also still have a role, and of course rail will also benefit (though to a lesser degree) from self-driving technology. SDVs would also help solve passenger rail’s “last mile problem”, as riders could simply order an SDV on their mobile phone from the train, to have it waiting for them at the next station.

On the downside, eliminating traffic lights in favour of traffic-dodging syncronized turns would be intimidating to pedestrians. This is one of my few concerns on the impact of SDVs. Also streets could become so thick and fast with SDVs that they’d no longer be attractive to pedestrians. I don’t have any easy answer for this one!

Important stuff to think about, and coming sooner than we ever imagined!

– Marcus Garnet, Senior Planner, Halifax, Canada